Mann Gulch: The fire that changed everything

Seventy-five years ago, earth and sky turned into fire.

The flames of the Mann Gulch fire spread rapidly, overtaking 16 men sent to tame it in a gulch outside of Helena. Just three survived.

The smokejumpers lost to the flames in the Gates of the Mountains Wild Area on Aug. 5, 1949 included two Kalispell natives, Henry Thol Jr. and William Hellman. A third man, Philip McVey, is buried in Ronan.

The deadly fire didn’t just scar the land, it also reshaped how wildland crews prepare for and battle wildfires.

“Although young men died like squirrels in Mann Gulch, the Mann Gulch fire should not end there, smoke drifting away and leaving terror without consolation of explanation, and controversy without lasting settlement,” wrote author Norman MacLean in his book detailing the event, “Young Men and Fire.” “This is a catastrophe that … might go on and become a story.”

That story, and its principal players, have taken center stage again this year. Events marking the anniversary of the conflagration are occurring throughout the state. In Kalispell, Thol and Hellman will be honored on Aug. 8, and McVey will be honored Aug. 10 at the Ronan Cemetery. The main honorary tribute in Helena was Aug. 5 at the Montana State Capitol building.

“The Mann Gulch fire was a catalyst for the formalization of the training and some of the tools — the thinking tools — that firefighters use to address safety. It was a catalyst for fire research,” said Carl Seielstad, fire and fuels manager and associate professor at the University of Montana’s Fire Center.

Sparked by dry lightning, the fire started on a day with low humidity and temperatures in the high-90s. Wind shifts and fuel types quickly changed its behavior. At the bottom of the hill, the firefighters couldn’t see what was happening.

When the team arrived, the flames covered between 50 and 60 acres. Most smokejumpers on the mission had never seen a fire that large.

By the time the fire was under control, it had burned 4,500 acres, between 7 and 8 square miles, and taken the effort of 450 men, MacLean wrote.

There are 10 standard firefighting orders that provide wildland crews with a set of best practices for fire response. Many stem from lessons learned at the Mann Gulch fire, according to Chiara Cipriano, Forest Service spokesperson.

Those include staying informed on fire weather conditions and knowing what the fire is doing, both tactics that could have saved lives 75 years ago. The weather on that August day saw perfect conditions for a fire.

“You need this freakish alignment of like 20 things for a fire like Mann Gulch to happen,” Seielstad said.

On Aug. 5, 1949 they aligned, he said.

The fire exploded due to a blowup, a concept that officials better understood after Mann Gulch. A blowup to a forest fire is something like a hurricane to an ocean storm, MacLean wrote in his book.

The suddenly expanding fire cut off the men’s route to the Missouri River and forced them back uphill as it climbed fiercely behind them.

It was later estimated that the fire covered 3,000 acres in 10 minutes.

A Forest Service employee also died while investigating the fire.

Today, the Forest Service and other groups use lookouts and communication between ground teams — while constantly watching weather conditions — to determine if it is safe for firefighters to go on the attack.

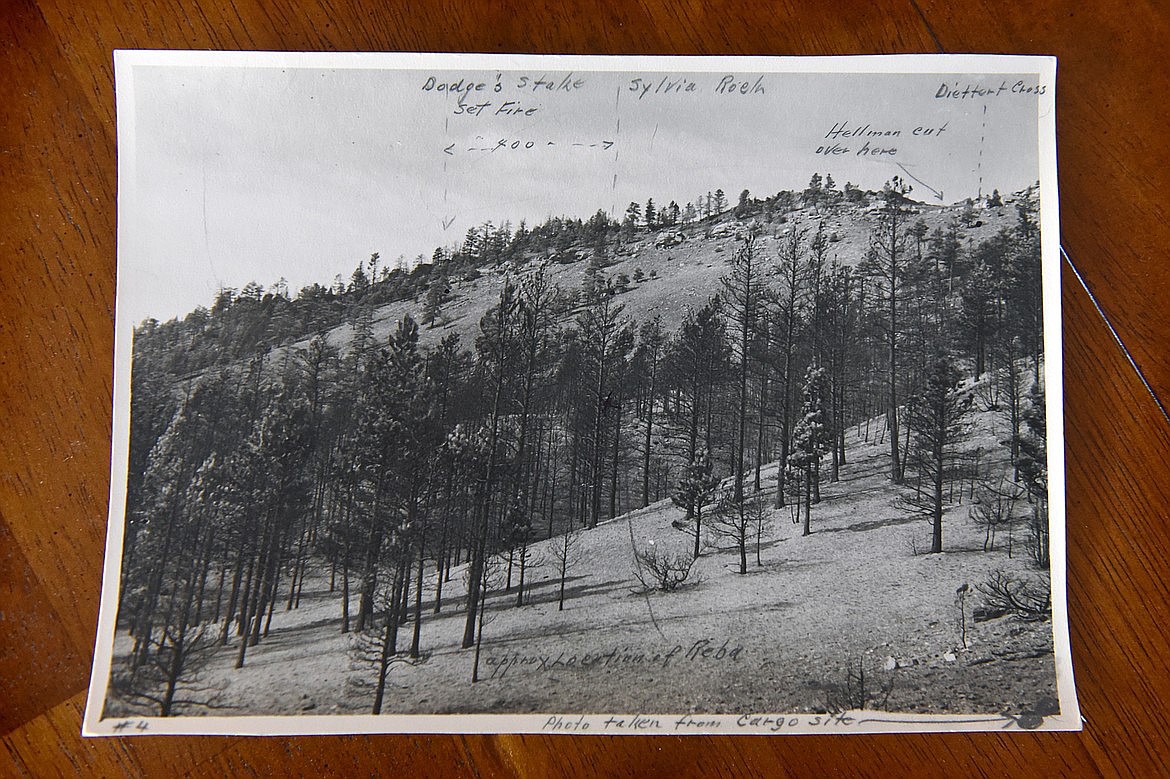

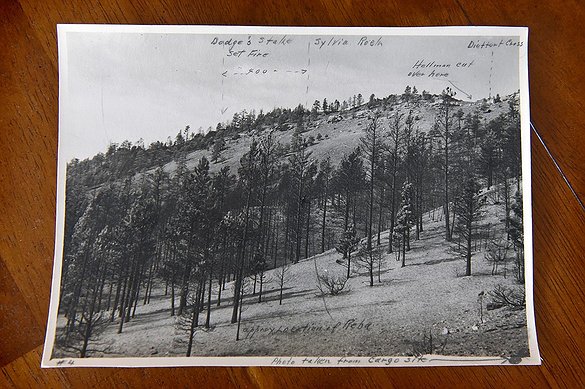

As the smokejumper team fled, foreman Wag Dodge, one of the only survivors, lit his own fire ahead of Mann Gulch’s flames. The first of its kind, it became known as an “escape fire.”

Dodge laid face down in the ashes of the fire he made as the Mann Gulch fire passed over him, breathing in the last of the oxygen found on the hot ground. Dodge called out for the other firefighters to join him. None of them did, likely because they didn’t know what was happening.

The escape fire tactic was initially deemed controversial by some members of the public, including Kalispell smokejumper Henry Thol Jr.’s father, Henry Thol Sr.

Thol Sr., a retired Forest Service district ranger, believed Dodge’s fire was responsible for the death of the other smokejumpers as they ran up the ridge.

His son, Thol Jr., was found closest to the top of Mann Gulch ridge after the fire, showing he made it farther to supposed safety than to the rest of his comrades.

The Forest Service ultimately cleared Dodge of responsibility and instead highlighted the escape fire for saving his life, and possibly saving more that day had a plan been communicated.

Dodge never performed another jump. He died of cancer in 1955.

Today, firefighting standard orders state that teams must identify escape routes and safety zones and then communicate clear instructions on escape plans before a fire attack starts, making sure everyone understands.

CHANGE TOOK time, Seielstad said. The publishing of MacLean’s book had a big impact on elevating the Mann Gulch fire into something with more significance, he said.

The way agencies fight wildfires continues to adapt with additional failures and successes; the memories of those who lost their lives at Mann Gulch continue.

“I think [this year] is a chance to reflect on the actual men themselves and just recognize the huge ripple effect that their lives had on this industry,” Cipriano said. “Safety always has to come first. The safety of people is huge.” Henry J. Thol, Jr. was born in 1930. The summer of 1949 was the second summer Thol worked with the Forest Service and his first as a smokejumper. He was 19 years old when he arrived at Mann Gulch.

Before the fire, Thol hoped to enroll at the University of Montana with his income as a smokejumper.

The smokejumper organization was just nine years old in 1949, a relatively new and dangerous job that was mostly staffed by young men, 10 of them military veterans.

Philip R. McVey, born in 1927, spent most of his childhood living along the Canadian border. A veteran, he joined the U.S. Navy for the last year of World War II before going to the University of Montana. The summer of 1949 was Philip’s fifth season with the Forest Service, where he worked clearing trails, and his second season as a smokejumper.

He was 22 at the time of the Mann Gulch fire.

William J. Hellman was born in 1925. Second in command to Dodge, Hellman was a veteran of World War II, serving in the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. Earlier in 1949, he was among an elite group of smokejumpers to perform a ceremonial jump onto the White House lawn.

Hellman made it to the ridge on Aug. 5 but succumbed to his injuries in a Helena hospital the following day. When the survivors found him, his pants and shoes had burnt off.

“[Hellman’s] burned flesh had a terrific odor. He was in severe pain but took his experience magnificently. [His] courage made men weep,” said District Ranger John Jansson, who led the rescue team, according to McLean’s book.

THE SWITCH to focusing on the human costs of firefighting was important to accurately learn how to effectively — and safely — fight fires, according to Seielstad.

“We have a perception that we can control nature in ways that we can’t, and I think these accidents remind us that we can’t always,” he said.

The Forest Service and the National Smokejumper Association will honor each of the men who died at grave sites across the country this week. The memorial tribute for Thol Jr. and Hellman at C.E. Conrad Memorial Cemetery in Kalispell will be held on Aug. 8 at 11 a.m. and 11:30 a.m., respectively. The memorial tribute for Philip McVey is on Aug. 10 at 2 p.m. at the Ronan Cemetery in Ronan.

Brass plates have been added to the gravestones in recent weeks, picturing smokejumper wings, a parachute, and highlighting the event that took their lives.

“It is time to rededicate ourselves to the memory of these fine young men and the lesson they best taught us, that wildfires are, and always will be, dangerous and we must respect its potential to put a firefighter in harm’s way,” said Bob Sallee, who was one of three Mann Gulch fire survivors, at the 50th anniversary memorial. “Life is precious— and for some very short.”